Volume 31, Issue 2 (7-2022)

JGUMS 2022, 31(2): 84-101 |

Back to browse issues page

Research code: 13990045 IR.YAZD.REC.

Ethics code: 13990045 IR.YAZD.REC.

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Norouzi Zad Z, Bakhshayesh A, Salehzadeh Abarghoui M. The Role of Personality Traits and Lifestyle in Predicting Anxiety and Depression During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. JGUMS 2022; 31 (2) :84-101

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2428-en.html

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2428-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran. , abakhshayesh@yazd.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran. , abakhshayesh@yazd.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 6244 kb]

(616 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1368 Views)

Full-Text: (944 Views)

Introduction

In dealing with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, quarantine and some social gathering restrictions have been recommended. Although these measures could help reduce the rate of infection, restricting the participation of people in normal daily living activities, sports activities, and traveling can lead to some negative influences [3]. In the past pandemics, it was shown that severe restrictions such as self-quarantine caused depression and anxiety in people [4]. Depression and anxiety can weaken the immune system and make people vulnerable against diseases such as COVID-19 [5]. Several previous studies have shown that self-quarantine is a predictor of depressive symptoms [6, 7, 8]. One of the important variables associated with depression is personality [9]. The personality is defined as specific and explicit patterns of thinking, emotion and behavior which determine the personal traits of individuals in interacting with social environment [10]. Personality traits affect how we understand the external stressors such as health problems, and can play a role in responding to pandemics [11].

Pandemics have a negative impact on the health and cause sudden changes in lifestyle with social and economic consequences due to social distancing and self-quarantine [13]. One of the best ways to maintain the health and prevent diseases is to have health promoting behaviors [14]. Health promoting behaviors are voluntary behaviors for promoting physical and mental health [15].

According to the important role of personality traits and lifestyle on mental health, this study aims to evaluate the role of personality traits and health-promoting lifestyles in predicting anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. The question is whether personality traits or health-promoting lifestyles have a greater role in predicting anxiety and depression.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed during the fourth wave of COVID-19 outbreak and social restrictions in April 2021 in Najafabad, Iran on 225 people aged >18 years who were selected using a convenience sampling method. Questionnaires were distributed online by adding the links in virtual social channels and groups. Inclusion criteria were consent to participate, age >18 years, living in Najafabad city, while exclusion criteria were a history of depression and anxiety disorders before the outbreak, and return of incomplete questionnaires. In this regard, 8 people were excluded due to having a history of depression and anxiety before the COVID-19 outbreak, and finally the data of 217 questionnaires were analyzed. The used instruments in this study were Corona Disease Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression inventory, McCray and Costa’s Big-Five-Factor Inventory, and Walker’s Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile. Raw data were analyzed in SPSS v. 24 statistical software using descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation test, and multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

There was a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and depression (P<0.001), while the relationship of extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness with depression was significantly negative (P<0.05). There was a significant negative relationship between health-promoting lifestyles and depression (P<0.05) (Table 1).

.jpg)

Among the variables included in the regression model, neuroticism, extraversion, self-actualization and physical activity were significant predictors of depression and had the greatest effect on depression (P<0.05) (Table 2).

.jpg)

There was a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.01), while the relationship of extraversion, openness, and agreeableness with anxiety was significantly negative (P<0.05). There was no significant relationship between conscientiousness and COVID-19 anxiety (P>0.05). There was a significant negative relationship between health-promoting lifestyles and COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.05) (Table 1).

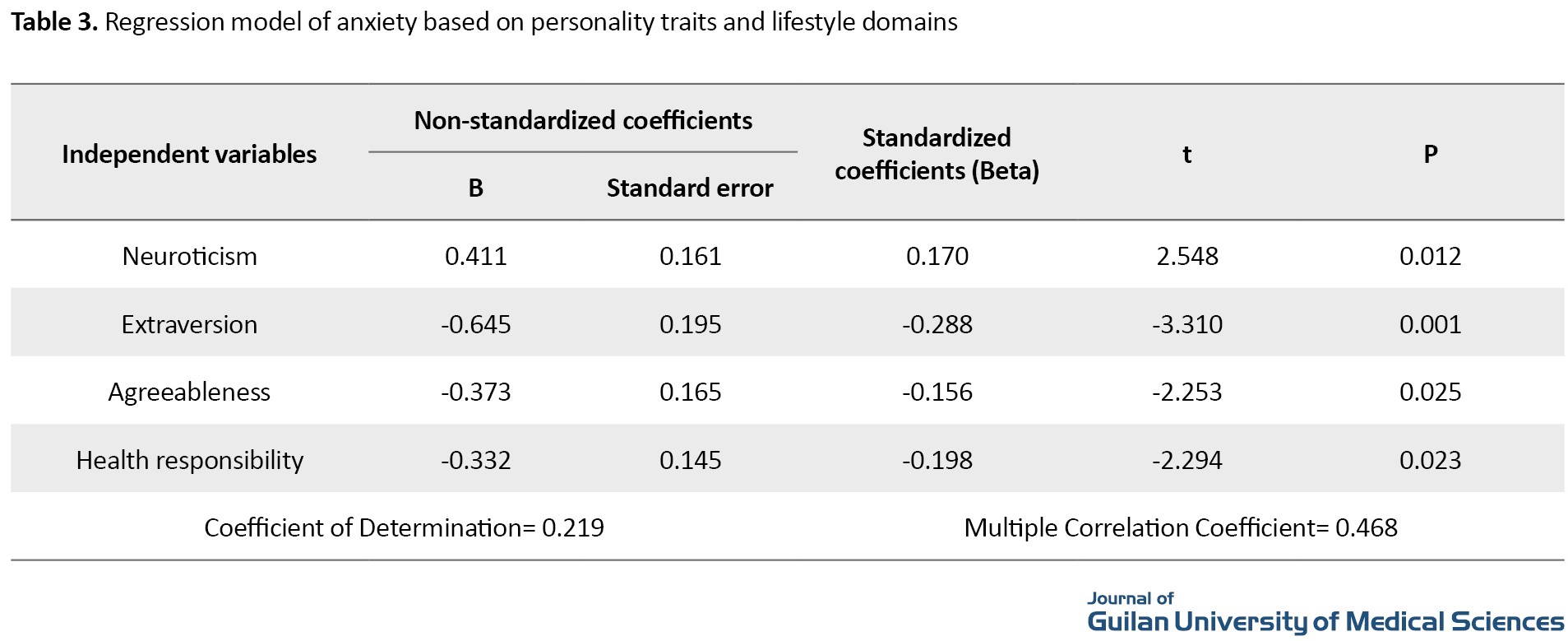

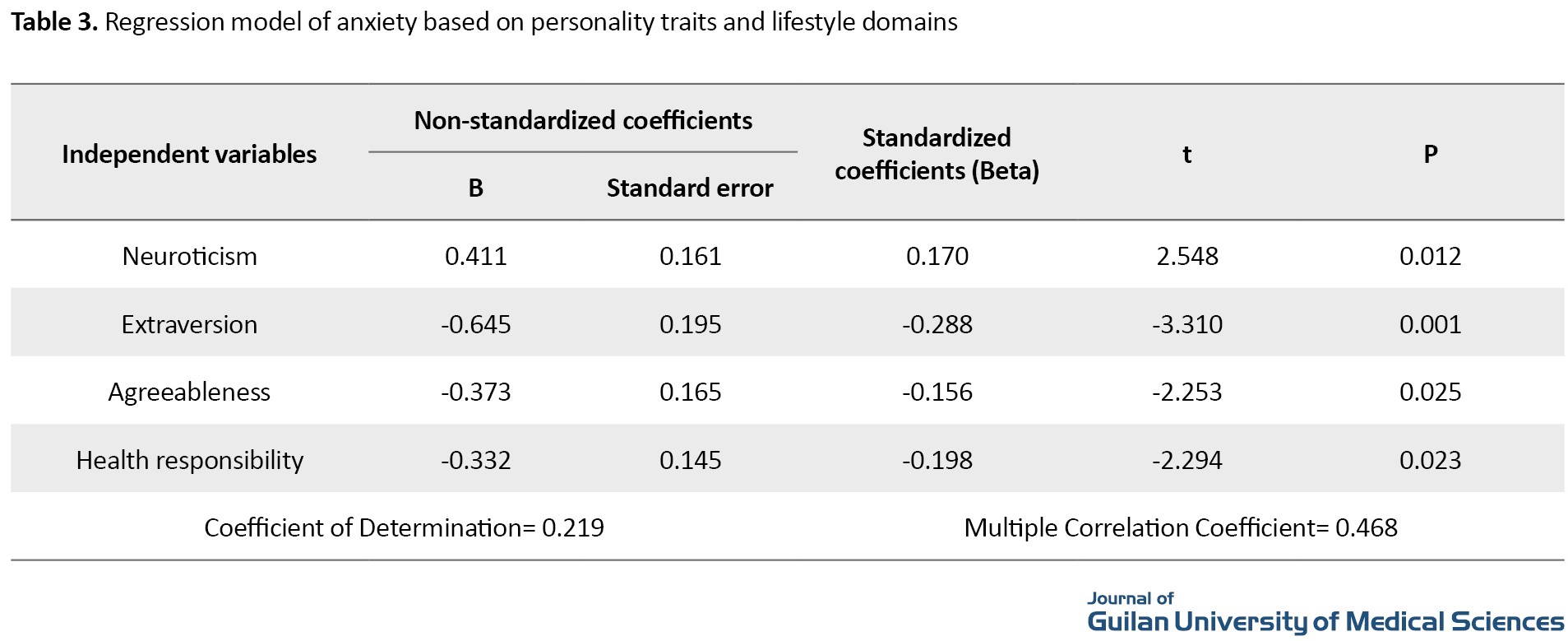

In the regression equation, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness and health responsibility were significant predictors of COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This results of the present study showed that the personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion were significant predictors of depression and COVID-19 anxiety. During the outbreak of COVID-19, a neurotic person may experience the greatest negative impact and the greatest amount of depression and anxiety. The extraversion trait composed of traits related to overall energy, assertiveness, sociability, and positive insight about future [38, 39]. The presence of these traits help extroverts deal with psychological consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak. This personality trait may play a role in activating copying mechanisms (e.g. communication with others, showing high spirits, etc.) [28]. The extroverts can obtain more social support in this period by using their verbal abilities and generating intimate relationships, resulting in their greater satisfaction and happiness.

The agreeableness personality trait was also the significant predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. With higher agreeableness trait, one can experience lower Covid-19 anxiety. It is expected that people with agreeableness, a positive attitude towards life, and greater adaptability to the conditions experience a greater sense of security and peace of mind than others during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Among the domains of health-promoting lifestyles, self-actualization and physical activity were the significant predictors of depression; i.e., by having more self-actualization and physical activity, people are less likely to be depressed. To explain this finding, we can refer to the increase in the secretion of endorphins and serotonin during physical activity which cause pleasant feelings and reduced depressive symptoms [44, 45]. Self-actualization plays an essential role in achieving positive well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic [50].

Health responsibility, as one of lifestyle domains, was a negative predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. It seems that people with higher health responsibility are more sensitive and cautious about their health during the outbreak, which causes a sense of relief about their health and not transmitting the disease to their relatives; this can lead to the experience of less anxiety.

Finally, regarding the study question, it can be said that the relationship of personality traits with COVID-19 anxiety and depression was greater compared to health-promoting lifestyle domains; and personality traits play a greater role in predicting anxiety and depression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Yazd University (Code: IR.YAZD.REC.1399.045)

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all people participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

In dealing with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, quarantine and some social gathering restrictions have been recommended. Although these measures could help reduce the rate of infection, restricting the participation of people in normal daily living activities, sports activities, and traveling can lead to some negative influences [3]. In the past pandemics, it was shown that severe restrictions such as self-quarantine caused depression and anxiety in people [4]. Depression and anxiety can weaken the immune system and make people vulnerable against diseases such as COVID-19 [5]. Several previous studies have shown that self-quarantine is a predictor of depressive symptoms [6, 7, 8]. One of the important variables associated with depression is personality [9]. The personality is defined as specific and explicit patterns of thinking, emotion and behavior which determine the personal traits of individuals in interacting with social environment [10]. Personality traits affect how we understand the external stressors such as health problems, and can play a role in responding to pandemics [11].

Pandemics have a negative impact on the health and cause sudden changes in lifestyle with social and economic consequences due to social distancing and self-quarantine [13]. One of the best ways to maintain the health and prevent diseases is to have health promoting behaviors [14]. Health promoting behaviors are voluntary behaviors for promoting physical and mental health [15].

According to the important role of personality traits and lifestyle on mental health, this study aims to evaluate the role of personality traits and health-promoting lifestyles in predicting anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. The question is whether personality traits or health-promoting lifestyles have a greater role in predicting anxiety and depression.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed during the fourth wave of COVID-19 outbreak and social restrictions in April 2021 in Najafabad, Iran on 225 people aged >18 years who were selected using a convenience sampling method. Questionnaires were distributed online by adding the links in virtual social channels and groups. Inclusion criteria were consent to participate, age >18 years, living in Najafabad city, while exclusion criteria were a history of depression and anxiety disorders before the outbreak, and return of incomplete questionnaires. In this regard, 8 people were excluded due to having a history of depression and anxiety before the COVID-19 outbreak, and finally the data of 217 questionnaires were analyzed. The used instruments in this study were Corona Disease Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression inventory, McCray and Costa’s Big-Five-Factor Inventory, and Walker’s Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile. Raw data were analyzed in SPSS v. 24 statistical software using descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation test, and multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

There was a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and depression (P<0.001), while the relationship of extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness with depression was significantly negative (P<0.05). There was a significant negative relationship between health-promoting lifestyles and depression (P<0.05) (Table 1).

.jpg)

Among the variables included in the regression model, neuroticism, extraversion, self-actualization and physical activity were significant predictors of depression and had the greatest effect on depression (P<0.05) (Table 2).

.jpg)

There was a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.01), while the relationship of extraversion, openness, and agreeableness with anxiety was significantly negative (P<0.05). There was no significant relationship between conscientiousness and COVID-19 anxiety (P>0.05). There was a significant negative relationship between health-promoting lifestyles and COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.05) (Table 1).

In the regression equation, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness and health responsibility were significant predictors of COVID-19 anxiety (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This results of the present study showed that the personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion were significant predictors of depression and COVID-19 anxiety. During the outbreak of COVID-19, a neurotic person may experience the greatest negative impact and the greatest amount of depression and anxiety. The extraversion trait composed of traits related to overall energy, assertiveness, sociability, and positive insight about future [38, 39]. The presence of these traits help extroverts deal with psychological consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak. This personality trait may play a role in activating copying mechanisms (e.g. communication with others, showing high spirits, etc.) [28]. The extroverts can obtain more social support in this period by using their verbal abilities and generating intimate relationships, resulting in their greater satisfaction and happiness.

The agreeableness personality trait was also the significant predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. With higher agreeableness trait, one can experience lower Covid-19 anxiety. It is expected that people with agreeableness, a positive attitude towards life, and greater adaptability to the conditions experience a greater sense of security and peace of mind than others during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Among the domains of health-promoting lifestyles, self-actualization and physical activity were the significant predictors of depression; i.e., by having more self-actualization and physical activity, people are less likely to be depressed. To explain this finding, we can refer to the increase in the secretion of endorphins and serotonin during physical activity which cause pleasant feelings and reduced depressive symptoms [44, 45]. Self-actualization plays an essential role in achieving positive well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic [50].

Health responsibility, as one of lifestyle domains, was a negative predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. It seems that people with higher health responsibility are more sensitive and cautious about their health during the outbreak, which causes a sense of relief about their health and not transmitting the disease to their relatives; this can lead to the experience of less anxiety.

Finally, regarding the study question, it can be said that the relationship of personality traits with COVID-19 anxiety and depression was greater compared to health-promoting lifestyle domains; and personality traits play a greater role in predicting anxiety and depression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Yazd University (Code: IR.YAZD.REC.1399.045)

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all people participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

- World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

- Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiology and Health. 2020; 42:e2020038.[DOI:10.4178/epih.e2020038] [PMCID]

- Bae JM. A suggestion for quality assessment in systematic reviews of observational studies in nutritional epidemiology. Epidemiology and Health. 2016; 38:e2016014. [DOI:10.4178/epih.e2016014] [PMCID]

- Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(4):e21. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0]

- Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatric Services. 2004; 55(9):1055-7. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055]

- Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004; 10(7):1206-12. [PMCID]

- Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: Lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012; 53(1):15-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003] [PMCID]

- Bayrami M, Gholizadeh H. [The personality factors as predictors for (Persian)]. Studies in Medical Sciences. 2011; 22(2):92-8. [Link]

- Atkinson RC, Hilgard E. Atkinson & Hilgard’s introduction to psychology. [H. Rafiei, Persian trans]. Tehran: Arjmand Publications; 2014. [Link]

- McCrae RR, Terracciano A. Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer's perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005; 88(3):547-61. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547]

- Plasker E. The 100 Year Lifestyle: Dr. Plasker's breakthrough solution for living your best life-every day of your life!. New York: Adams Media; 2007. [Link]

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, Attinà A, Cinelli G, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020; 18(1):229. [DOI:10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5] [PMCID]

- Hosseini Z, Aghamolaei T, Ghanbarnejad A. Prediction of health promoting behaviors through the health locus of control in a sample of adolescents in Iran. Health Scope. 2017; 6(2):e39432. [DOI:10.5812/jhealthscope.39432]

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. New York: Pearson publishing; 2019. [Link]

- Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020; 92(5):479-90. [DOI:10.1002/jmv.25707] [PMCID]

- Lippi G, Henry BM, Sanchis-Gomar F. Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2020; 27(9):906-8. [DOI:10.1177/2047487320916823] [PMCID]

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020; 12(6):1583.[DOI:10.3390/nu12061583] [PMCID]

- Gatezadeh A, Eskandari, H. [Test causal model of depression on lifestyle through the mediation of social health and quality of life in adults in Ahvaz (Persian)]. Psychological Methods and Models. 2018; 8(30):123-40. [Link]

- Ramos-Grille I, Aragay N, Valero S, Garrido G, Santacana M, Guillamat R, et al. Relationship between depressive disorders and personality traits: The value of the alternative five factor model. Current Psychology. 2020; 1-7. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-020-01005-7]

- Nouri F, Feizi A, Afshar H, HassanzadehKeshteli A, Adibi P. How five-factor personality traits affect psychological distress and depression? Results from a large population-based study. Psychological Studies. 2019; 64(1):59-69. [DOI:10.1007/s12646-018-0474-6]

- Alipour A, Ghadami A, Alipour Z, Abdollahzadeh H. [Preliminary validation of the corona disease anxiety scale (CDAS) in the Iranian sample (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Health Psychology. 2020; 8(32):163-75. [Link]

- Desmet M, Vanheule S, Verhaeghe P. Dependency, self-criticism, and the symptom specificity hypothesis in a depressed clinical sample. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2006; 34(8):1017-26. [DOI:10.2224/sbp.2006.34.8.1017]

- Fairbrother N, Moretti M. Sociotropy, autonomy, and self-discrepancy: Status in depressed, remitted depressed, and control participants. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1998; 22(3):279-97. [DOI:10.1023/A:1018796810260]

- Fathiashtiani A, Dastani, M. Psychological tests of personality and mental health evaluation. Tehran: Besat Publications; 2016. [Link]

- McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality. 1992; 60(2):175-215. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x]

- Mohammadizeidi I, Pakpourhajiagha A, Mohammadizeidi B. [Reliability and validity of Persian version of the health-promoting lifestyle profile (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2012; 21(1):102-13. [Link]

- Nikčević AV, Marino C, Kolubinski DC, Leach D, Spada MM. Modelling the contribution of the big five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 279:578-84.[DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.053] [PMCID]

- Gong Y, Shi J, Ding H, Zhang M, Kang C, Wang K, et al. Personality traits and depressive symptoms: The moderating and mediating effects of resilience in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 265:611-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.102]

- Kenter E. School pressure and depressive thoughts in early and middle adolescence and the moderating effect of personality traits and sex [MA thesis]. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2019. [Link]

- JJourdy R, Petot JM. Relationships between personality traits and depression in the light of the “Big Five” and their different facets. L'évolution Psychiatrique. 2017; 82(4):e27-37.[DOI:10.1016/j.evopsy.2017.08.002]

- SSami AH, Naveeda N. An examination of depressive symptoms in adolescents: The relationship of personality traits and perceived social support. Islamic Guidance and Counseling Journal. 2021; 4(1):1-11. [DOI:10.25217/igcj.v4i1.848]

- Mobarakiasl N, Mirmazhari R, Dargahi R, Hadadi Z, Montazer M. [Relationships among personality traits, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer (Peresian)]. Iranian Quarterly Journal of Breast Disease. 2019; 12(3):60-71. [DOI:10.30699/acadpub.ijbd.12.3.60]

- Rezaei M, GHolamrezayi S, Sepahvandi M, Ghazanfari F, Darikvand F. [The potency of early maladaptive schemas and personality dimensions in prediction of depression (Persian)]. Thoughts and Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 2013; 8(29): 77-86. [Link]

- Vossoughi A, Bakhshipour Roodsari A, Hashemi T, Fathollahi S. [Structural associations of NEO personality dimensions with symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology. 2012; 18(3):233-44. [Link]

- Nudelman G, Kamble SV, Otto K. Can personality traits predict depression during the COVID-19 pandemic? Social Justice Research. 2021; 34(2):218-34. [DOI:10.1007/s11211-021-00369-w] [PMCID]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987; 52(1):81-90. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81]

- King EB, George JM, Hebl MR. Linking personality to helping behaviors at work: An interactional perspective. Journal of Personality. 2005; 73(3):585-607. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00322.x]

- Roccas S, Sagiv L, Schwartz SH, Knafo A. The big five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002; 28(6):789-801.[DOI:10.1177/0146167202289008]

- Garre-Olmo J, Turró-Garriga O, Martí-Lluch R, Zacarías-Pons L, Alves-Cabratosa L, Serrano-Sarbosa D, et al. Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: A cross-sectional a population-based study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2021; 104:152214.[DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152214] [PMCID]

- Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: Associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4065. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17114065] [PMCID]

- Ogawa S, Kitagawa Y, Fukushima M, Yonehara H, Nishida A, Togo F, et al. Interactive effect of sleep duration and physical activity on anxiety/depression in adolescents. Psychiatry Research. 2019; 273:456-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.085]

- Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S, Sadoff S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021; 118(9):e2016632118. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.2016632118] [PMCID]

- Grohol JM. Depression in women, seniors and children [Internet]. 2007 [Cited 2007 Sep. 7].

- Smith LL. Elliott CH. Depression for dummies. New York: Wiley Publishing; 2003. [Link]

- Bahar A, Shahriary M, Fazlali M. Effectiveness of Logotherapy on death anxiety, hope, depression, and proper use of glucose control drugs in diabetic patients with depression. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2021; 12:6 [DOI:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_553_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lane JA. The care of the human spirit. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1987; 3(6):332-7. [DOI:10.1016/S8755-7223(87)80121-7]

- Travis JW, Ryan RS. The wellness workbook. California: Ten Speed Press; 1981. [Link]

- Maslow A. Self-actualizing and Beyond. Conference on the Training of Counselors of Adults. 1967 22-28 May: Massachusetts. USA. [Link]

- Del Castillo FA. Self-actualization towards positive well-being: Combating despair during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health. 2021; 43(4):e757-e758. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdab148] [PMCID]

- Abbasi-Asl R, Naderi H, Akbari A. [Predicting female students’ social anxiety based on their personality traits (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2016; 18(6):343-9. [10.22038/JFMH.2016.7808]

- Ghorbani V, Jandaghiyan M, Jokar S, Zanjani Z. [The prediction of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 outbreak based on personality traits in the residents of Kashan city from March to April 2020: A descriptive study (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2021; 20(5):503-18. [DOI:10.52547/jrums.20.5.503]

- McCrae RR. The five-factor model and its assessment in clinical settings. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991; 57(3):399-414. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5703_2]

- Berdan LE, Keane SP, Calkins SD. Temperament and externalizing behavior: Social preference and perceived acceptance as protective factors. Development Psychology. 2008; 44(4):957-68. [DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.957] [PMCID]

- Connolly I, O'Moore M. Personality and family relations of children who bully. Personality and individual differences. 2003; 35(3):559-67. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00218-0]

- Basharpoor S, Heydarirad H, Atadokht A, Daryadel SJ, Nasiri-Razi R. The role of health beliefs and health promoting lifestyle in predicting pregnancy anxiety among pregnant women. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2015; 3(3):171-80. [Link]

- Kelly DL, Yang GS, Starkweather AR, Siangphoe U, Alexander-Delpech P, Lyon DE. Relationships among fatigue, anxiety, depression, and pain and health-promoting lifestyle behaviors in women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2020; 43(2):134-46. [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000676]

- Farivar M, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S. The role of health promoting behaviors and health beliefs in predicting of corona anxiety (COVID-19) among nurses. Quarterly Journal of Nersing Management. 2021; 9(4):1-10. [Link]

- Fathi A, Sadeghi S, Malekirad AA, Rostami H, Abdolmohammadi K. [Effect of health-promoting lifestyle and psychological well-being on anxiety induced by coronavirus disease 2019 in non-medical students (Persian)]. Journal of Arak University of Medical Sciences. 2020; 23(5):698-709. [DOI:10.32598/jams.23.cov.1889.2]

Review Paper: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2021/11/20 | Accepted: 2022/02/26 | Published: 2022/07/1

Received: 2021/11/20 | Accepted: 2022/02/26 | Published: 2022/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |