Volume 32, Issue 4 (1-2024)

JGUMS 2024, 32(4): 318-333 |

Back to browse issues page

Research code: ir.urmia.rec.1400.002

Ethics code: ir.urmia.rec.1400.002

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

ali golzadeh kenarsari A, yakhchali M, Ashrafi Fashi K, Sharifdini M. Prevalence of Cercariae Infection in Snails From the Lymnaeidae and Physidae Families in Aquatic Regions of Guilan Province, Northern Iran, and the Effect of Some Physicochemical Parameters of Water on Snail Abundance and Infection Rate. JGUMS 2024; 32 (4) :318-333

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2584-en.html

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2584-en.html

1- PhD candidate Parasitology, Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran. Email: armin_aligolzadeh@yahoo.com

2- Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran. (corresponding author) Email: m.yakhchali@urmia.ac.ir

3- Department of Microbiology, Parasitology and Immunology, Medical Sciences, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran. Email: k_fashi@yahoo.com

4- Department of Microbiology, Parasitology and Immunology, Medical Sciences, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran. Email: sharifdini5@gmail.com

2- Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran. (corresponding author) Email: m.yakhchali@urmia.ac.ir

3- Department of Microbiology, Parasitology and Immunology, Medical Sciences, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran. Email: k_fashi@yahoo.com

4- Department of Microbiology, Parasitology and Immunology, Medical Sciences, Guilan University, Rasht, Iran. Email: sharifdini5@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 5407 kb]

(586 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1805 Views)

Full-Text: (1575 Views)

Introduction

Infection with trematodes is important for the hygiene and health of humans and animals, and can negatively affect the agriculture and livestock economy [1]. Snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families, as groups of the order Basommatophora, have an important role in the evolution and transmission of parasitic trematodes. About 18,000 species of trematodes use snails as their first intermediate host [2]. Snails of the Lymnaeidae family live in stagnant water with slow water flow, more oxygen, lower temperatures, and suitable vegetation. Forty species of snails from the Lymnaeidae family have been found, of which 7 have been identified in Iran, where the dominant species was Lymnaea auricularia [3]. Due to the average temperature, high annual rainfall, and high relative humidity, the area around the Caspian Sea is a very favorable habitat for the growth and reproduction of snails. The present study aims to determine the diversity and cercariae infection in the snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families in Guilan province, northern Iran, and assess the effects of physicochemical parameters of water on their abundance and distribution.

Methods

Locating and sampling the freshwater snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families was done using a cluster random sampling method from 117 regions in the aquatic habitats of Guilan province (reservoirs, canals, rivers and agricultural lands) from June 2021 to June 2022. The snails were identified based on morphometric identification keys [4]. Water temperature was measured and recorded with a mercury thermometer at the place and time of the sample. Water pH was measured using a pH meter; electrical conductivity (EC) was measured using an EC meter, and salinity was measured using a salinity meter. In the laboratory, the found snails were poured into a 100-mesh sieve and washed with a pestle to remove mud, foreign objects, and plants. To identify and recognize the morphology of snails, the right-handed and left-handed snails were first placed separately in a 24-well cell culture plate, and 1 mL of deionized water was added to it. A hole was created on the lid at the top of each well for air exchange. To remove the cercariae of the snails, the cell culture plates containing the snails were transferred to a refrigerated incubator at a temperature of 20 °C, and the removal of cercariae was stimulated with artificial light (10 watt LED lamp) [5]. To check the morphological characteristics of the cercariae, 10 μL of the liquid inside the wells was placed on the slide, and after adding 0.5% vital dye, it was covered with the slide. These samples were studied under an optical microscope and identified using the cercariae identification key.

Results

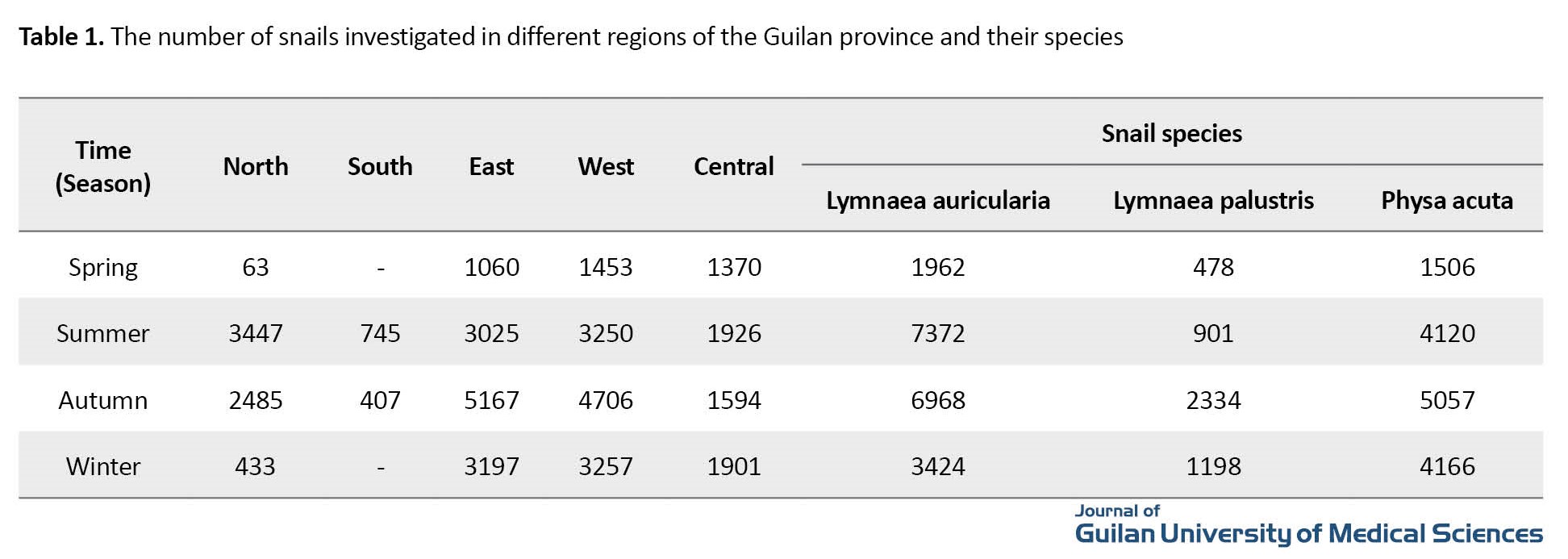

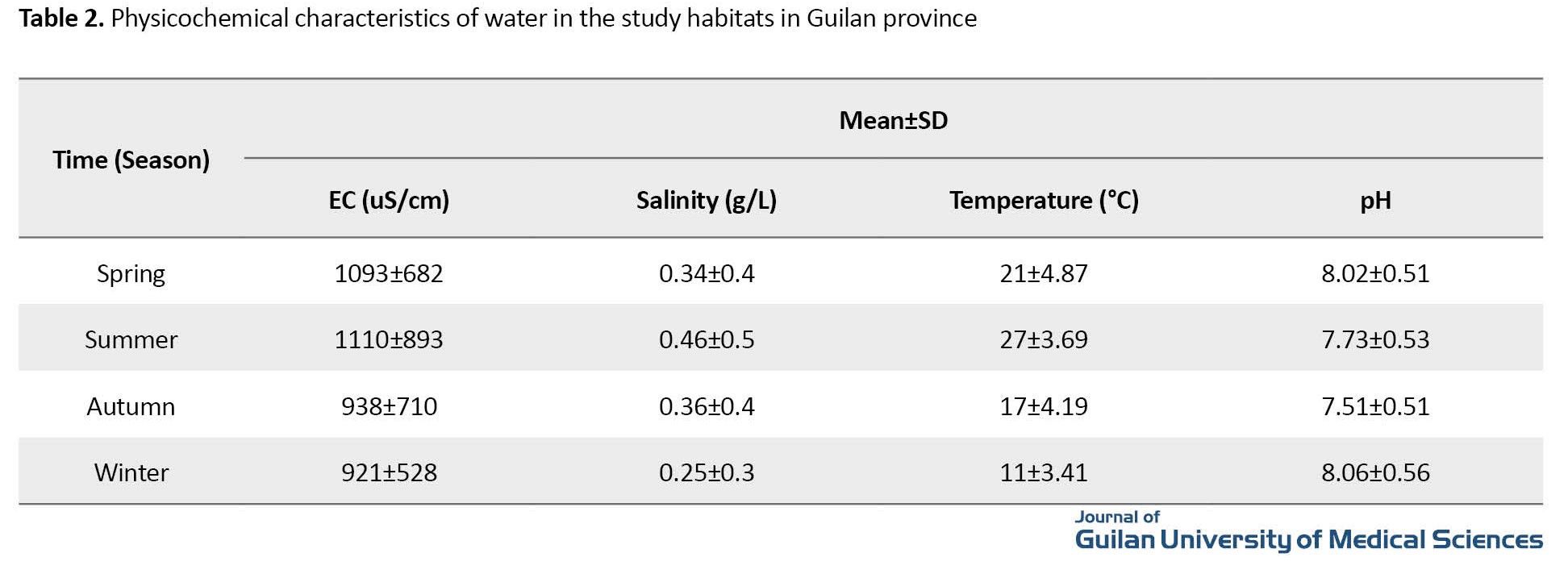

Out of 39486 snails, 19726 were lymnaea auricularia (49.96%), 4911 were lymnaea palustris (12.44%), and 14849 were Physa acuta (37.6%) (Table 1).

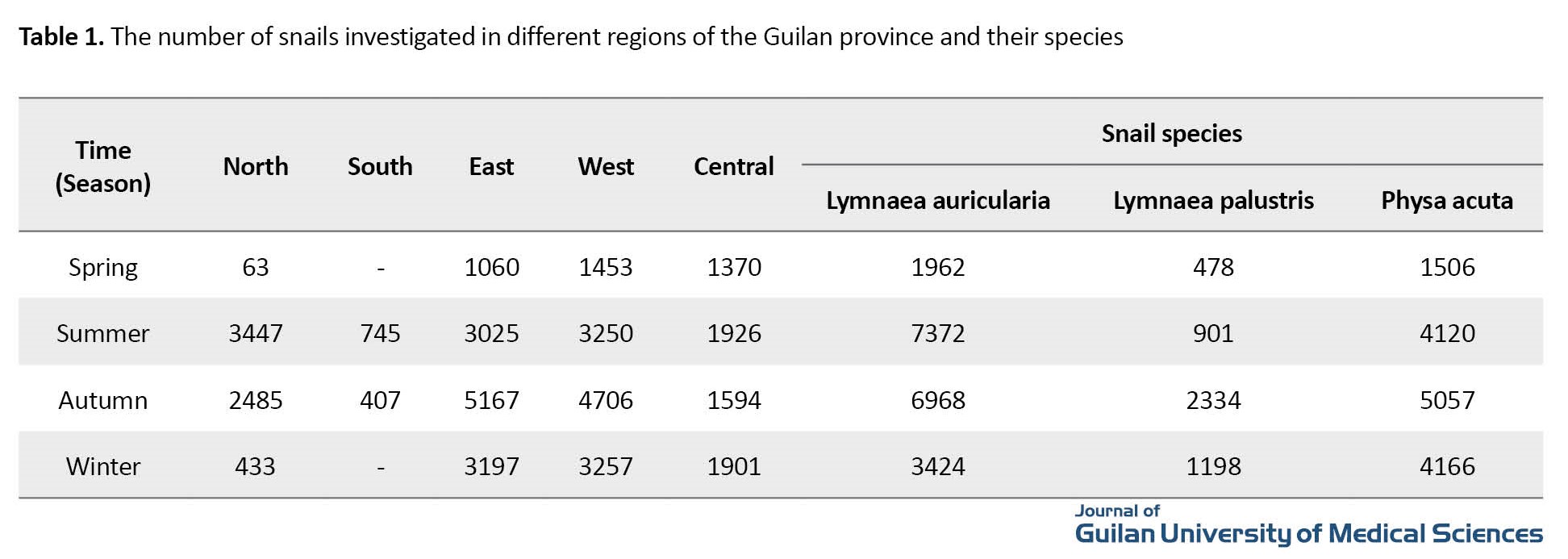

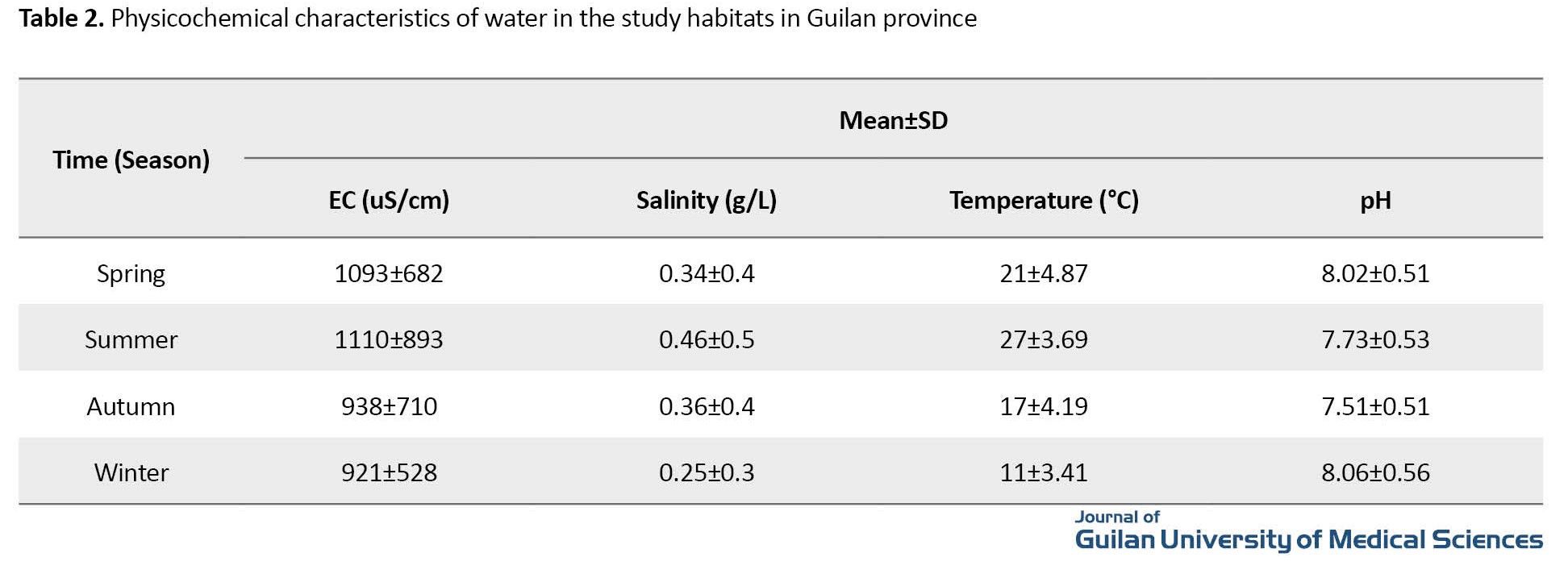

The prevalence of trematode cercariae infection in snails was 2.36%, (3.65% in lymnaea auricularia, 4.29% in lymnaea palustris, and none in Physa acuta). The identified cercariae were from the groups of Xiphidiocercariae (0.94%), Gymnocephalous (0.02%), Echinostome (0.8%), Lophocercous (0.16%), and Furcocercous (0.44%). The abundance of snails was 36.36% in the autumn, 31.39% in the summer, 22.25% in the winter, and 10% in the spring. The prevalence of infection in the snail lymnaea auricularia with Xiphidiocercariae was 1.58%; with Gymnocephalous, 0.04%; with Echinostome, 1.28%; with Lophocercous, 0.32%; and with Furcocercous, 0.43%. The prevalence of infection in the snail Lymnaea palustris with Xiphidiocercariae was 1.11%; with Echinostome, 1.39%; and with Furcocercous, 1.79%. There was no cercaria contamination in the snail Physa acuta. The one-year prevalence of infection in snails was 32.97% in spring, 28.28% in summer, 15.95% in autumn, and 22.8% in winter. The highest prevalence of infection with Xiphidiocercariae, Gymnocephalous, and Echinostome was in the summer (1.32, 0.04%, and 1.07%, respectively), while the highest prevalence of infection with Lophocercous and Furcocercous was in the autumn (0.19%) and the spring (1.78%), respectively. The variables of water temperature and waster pH had a significant negative relationship with the prevalence of cercariae infection in snails (P<0.05) (Table 2).

The abundance of snail had a significant positive relationship with the variables of water salinity and water EC (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Conclusion

Snails from the Lymnaeidae family are of great medical and veterinary importance because they play an important role in the life cycle of trematodes. In this study, the abundance of snails and the prevalence of infection in them were higher in the summer and autumn seasons than in winter and spring. Xiphidiocercariae, Gymnocephalous, Echinostome, Lophocercous and Furcocercous cercariae were isolated from the Lymnaeidae snails. In this study, two species of lymnaea auricularia and lymnaea palustris were identified from the Lymnaeidae family; from the Physidae family, Physa acuta was identified. In this study, water salinity had a significant direct relationship with the abundance of snail, while in another study, the increase in water salinity caused a decrease in the population of snails [6]. In our study, there was an negative significant relationship between the prevalence of cercariae infection in snails and water temperature, but water temperature had no relationship with the abundance of snails. There was a significant relationship between water pH and the prevalence of infection, but water pH was not related to the abundance of snails. This findings are consistent with Soldanova’s report in 2010 [7]. In Mazandaran province of Iran, 3.9% of lymnaea auricularia snails were infected with cercaria trematodes from the Plagiorchiida, Diplostomidae, Clinostomidae and Echinostomatidae families. In the study by Imani et al [8] in 2013, dor Lymnaea gedrosiana snails, the prevalence of infection was reported 8.03% (81.98% with Xiphidiocercariae, 32.26% with Furcocercous, 5.19% with Echinostoma, and 1.24% with Monostomes) in the northwest of Iran [9]. In a recent study conducted in Guilan province, species of Lymnaea auricularia, Lymnaea gedrosiana, Lymnaea palustris, Lymnaea trancatula, Lymnaea stagnalis, Physa acuta and Planorbis species were identified, where infection with Gymnocephalus was observed in Lymnaea auricularia (0.66%) and Lymnaea gedrosiana (0.45%) [10]. This study in Guilan province with many water resources, environmental conditions and geographical areas suitable for the breeding of snails, and the occurrence of large epidemics of parasitic diseases can be important from a medical and veterinary point of view. More studies are recommended in this field.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Urmia University (Ethics Code: IR.URMIA.REC.1400.002).

Funding

This study was funded by the Urmia University.

Authors' contributions

Study concept and design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, critical revision, administrative, technical, or material support, and study supervision: All authors; Drafting of the manuscript, funding acquisition: Armin Aligolzadeh Kenarsari and Mohammad Yakhchali; Statistical analysis: Armin Aligolzadeh Kenarsari, Mohammad Yakhchali, Keyhan Ashrafi Fashi.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Urmia University and Guilan University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation in this study.

References

Infection with trematodes is important for the hygiene and health of humans and animals, and can negatively affect the agriculture and livestock economy [1]. Snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families, as groups of the order Basommatophora, have an important role in the evolution and transmission of parasitic trematodes. About 18,000 species of trematodes use snails as their first intermediate host [2]. Snails of the Lymnaeidae family live in stagnant water with slow water flow, more oxygen, lower temperatures, and suitable vegetation. Forty species of snails from the Lymnaeidae family have been found, of which 7 have been identified in Iran, where the dominant species was Lymnaea auricularia [3]. Due to the average temperature, high annual rainfall, and high relative humidity, the area around the Caspian Sea is a very favorable habitat for the growth and reproduction of snails. The present study aims to determine the diversity and cercariae infection in the snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families in Guilan province, northern Iran, and assess the effects of physicochemical parameters of water on their abundance and distribution.

Methods

Locating and sampling the freshwater snails from the Lymnaeidae and Physidae families was done using a cluster random sampling method from 117 regions in the aquatic habitats of Guilan province (reservoirs, canals, rivers and agricultural lands) from June 2021 to June 2022. The snails were identified based on morphometric identification keys [4]. Water temperature was measured and recorded with a mercury thermometer at the place and time of the sample. Water pH was measured using a pH meter; electrical conductivity (EC) was measured using an EC meter, and salinity was measured using a salinity meter. In the laboratory, the found snails were poured into a 100-mesh sieve and washed with a pestle to remove mud, foreign objects, and plants. To identify and recognize the morphology of snails, the right-handed and left-handed snails were first placed separately in a 24-well cell culture plate, and 1 mL of deionized water was added to it. A hole was created on the lid at the top of each well for air exchange. To remove the cercariae of the snails, the cell culture plates containing the snails were transferred to a refrigerated incubator at a temperature of 20 °C, and the removal of cercariae was stimulated with artificial light (10 watt LED lamp) [5]. To check the morphological characteristics of the cercariae, 10 μL of the liquid inside the wells was placed on the slide, and after adding 0.5% vital dye, it was covered with the slide. These samples were studied under an optical microscope and identified using the cercariae identification key.

Results

Out of 39486 snails, 19726 were lymnaea auricularia (49.96%), 4911 were lymnaea palustris (12.44%), and 14849 were Physa acuta (37.6%) (Table 1).

The prevalence of trematode cercariae infection in snails was 2.36%, (3.65% in lymnaea auricularia, 4.29% in lymnaea palustris, and none in Physa acuta). The identified cercariae were from the groups of Xiphidiocercariae (0.94%), Gymnocephalous (0.02%), Echinostome (0.8%), Lophocercous (0.16%), and Furcocercous (0.44%). The abundance of snails was 36.36% in the autumn, 31.39% in the summer, 22.25% in the winter, and 10% in the spring. The prevalence of infection in the snail lymnaea auricularia with Xiphidiocercariae was 1.58%; with Gymnocephalous, 0.04%; with Echinostome, 1.28%; with Lophocercous, 0.32%; and with Furcocercous, 0.43%. The prevalence of infection in the snail Lymnaea palustris with Xiphidiocercariae was 1.11%; with Echinostome, 1.39%; and with Furcocercous, 1.79%. There was no cercaria contamination in the snail Physa acuta. The one-year prevalence of infection in snails was 32.97% in spring, 28.28% in summer, 15.95% in autumn, and 22.8% in winter. The highest prevalence of infection with Xiphidiocercariae, Gymnocephalous, and Echinostome was in the summer (1.32, 0.04%, and 1.07%, respectively), while the highest prevalence of infection with Lophocercous and Furcocercous was in the autumn (0.19%) and the spring (1.78%), respectively. The variables of water temperature and waster pH had a significant negative relationship with the prevalence of cercariae infection in snails (P<0.05) (Table 2).

The abundance of snail had a significant positive relationship with the variables of water salinity and water EC (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Conclusion

Snails from the Lymnaeidae family are of great medical and veterinary importance because they play an important role in the life cycle of trematodes. In this study, the abundance of snails and the prevalence of infection in them were higher in the summer and autumn seasons than in winter and spring. Xiphidiocercariae, Gymnocephalous, Echinostome, Lophocercous and Furcocercous cercariae were isolated from the Lymnaeidae snails. In this study, two species of lymnaea auricularia and lymnaea palustris were identified from the Lymnaeidae family; from the Physidae family, Physa acuta was identified. In this study, water salinity had a significant direct relationship with the abundance of snail, while in another study, the increase in water salinity caused a decrease in the population of snails [6]. In our study, there was an negative significant relationship between the prevalence of cercariae infection in snails and water temperature, but water temperature had no relationship with the abundance of snails. There was a significant relationship between water pH and the prevalence of infection, but water pH was not related to the abundance of snails. This findings are consistent with Soldanova’s report in 2010 [7]. In Mazandaran province of Iran, 3.9% of lymnaea auricularia snails were infected with cercaria trematodes from the Plagiorchiida, Diplostomidae, Clinostomidae and Echinostomatidae families. In the study by Imani et al [8] in 2013, dor Lymnaea gedrosiana snails, the prevalence of infection was reported 8.03% (81.98% with Xiphidiocercariae, 32.26% with Furcocercous, 5.19% with Echinostoma, and 1.24% with Monostomes) in the northwest of Iran [9]. In a recent study conducted in Guilan province, species of Lymnaea auricularia, Lymnaea gedrosiana, Lymnaea palustris, Lymnaea trancatula, Lymnaea stagnalis, Physa acuta and Planorbis species were identified, where infection with Gymnocephalus was observed in Lymnaea auricularia (0.66%) and Lymnaea gedrosiana (0.45%) [10]. This study in Guilan province with many water resources, environmental conditions and geographical areas suitable for the breeding of snails, and the occurrence of large epidemics of parasitic diseases can be important from a medical and veterinary point of view. More studies are recommended in this field.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Urmia University (Ethics Code: IR.URMIA.REC.1400.002).

Funding

This study was funded by the Urmia University.

Authors' contributions

Study concept and design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, critical revision, administrative, technical, or material support, and study supervision: All authors; Drafting of the manuscript, funding acquisition: Armin Aligolzadeh Kenarsari and Mohammad Yakhchali; Statistical analysis: Armin Aligolzadeh Kenarsari, Mohammad Yakhchali, Keyhan Ashrafi Fashi.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Urmia University and Guilan University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Ghobadi K, Yakhchali M . [Survey of liver helminthes infection rate and economic loss in sheep in Urmia slaughterhouse (Persian)]. Iranian Veterinary Jornal. 2005; 9(11):60-6. [Link]

- Littlewood DTJ, Bray RA. Interrelationships of the platyhelminthes. London: CRC Press; 2014. [Link]

- Zbikowska E, Nowak A. One hundred years of research on the natural infection of freshwater snails by trematode larvae in Europe. Parasitology Research. 2009; 105(2):301-11. [DOI:10.1007/s00436-009-1462-5] [PMID]

- Mansourian A. [Fresh water snail fauna of Iran (Persian)] [PhD desertation]. Tehran: Tehran Medical Sciences University, Iran; 1992.

- Kariuki HC, Clennon JA, Brady MS, Kitron U, Sturrock RF, Ouma JH, et al. Distribution patterns and cercarial shedding of Bulinus nasutus and other snails in the Msambweni area, Coast Province, Kenya. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004; 70(4):449-56. [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2004.70.449] [PMID]

- El-Kady GA, Shoukry A, Reda LA, El-Badri YS. Survey and population dynamics of freshwater snails in newly settled areas of the Sinai Peninsula. Egyptian Journal of Biology. 2000; 2:42-8. [Link]

- Żbikowska E. The effect of digenea larvae on calcium content in the shells of Lymnaea stagnalis (L.) individuals. Journal of Parasitology. 2003; 89(1):76-9. [DOI:10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0076:TEODLO]2.0.CO;2]

- Imani-Baran A, Yakhchali M, Malekzadeh Viayeh R, Farhangpajuh F. Prevalence of cercariae infection in Lymnaea auricularia (Linnaeus, 1758) in Northwest of Iran. Veterinary Research Forum. 2011; 2(2):121-7. [Link]

- Massoud J. Observations on Lymnaea gedrosiana, the intermediate host of Ornithobilharzia turkestanicum in Khuzestan, Iran. Journal of Helminthology. 1974; 48(2):133-8.[DOI:10.1017/S0022149X00022720] [PMID]

- Sharif M, Daryani A, Karimi SA. A faunistic survey of cercariae isolated from lymnaeid snails in central areas of Mazandaran, Iran. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2010; 13(4):158-63. [DOI:10.3923/pjbs.2010.158.163] [PMID]

- World Health Organization. Action against worms N°10: The "neglected" neglected worms. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Link]

- Salahi-Moghaddam A, Arfaa F. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis outbreaks in Iran. Journal of Archives in Military Medicine. 2013; 1(1):6-12. [DOI:10.5812/jamm.13890]

- Athari A, Gohar-Dehi S, Rostami-Jalilian M. Determination of definitive and intermediate hosts of cercarial dermatitis-producing agents in northern Iran. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2006; 9(1):11-5. [PMID]

- Salahi-Moghadam A, Mahvi AH, Molavi G, Hosseini-Chegeni A, Massoud J. [Parasitological study on lymnaea palustris and its ecological survey by gis in Mazandaran Province (Persian)]. Modares Journal of Medical Sciences. 2008; 11(3-4):65-71. [Link]

- Faltýnková A, Nasincová V, Kablásková L. Larval trematodes (Digenea) of planorbid snails (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) in Central Europe: A survey of species and key to their identification. Systematic Parasitology. 2008; 69(3):155-78. [DOI:10.1007/s11230-007-9127-1] [PMID]

- Imani-Baran A, Yakhchali M, Malekzadeh-Viayeh R, Farahnak A. Seasonal and geograpHic distribution of cercarial infection in Lymnaea gedrosiana (Pulmunata: Lymnaeidae) in North West Iran. Iranian Journal of Parasitology 2013; 8(3):423-9. [PMID]

- Galaktionov KV, Dobrovolskij A. The biology and evolution of trematodes: An essay on the biology, morpHology, life cycles, transmissions, and evolution of digenetic trematodes. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013. [Link]

- Chingwena G, Mukaratirwa S, Chimbari M, Kristensen TK, Madsen H. Population dynamics and ecology of freshwater gastropods in the highveld and lowveld regions of Zimbabwe, with emphasis on schistosome and ampHistome intermediate hosts. African Zoology. 2004; 39(1):55-62. [DOI:10.1080/15627020.2004.11407286]

- Imani-Baran A, Yakhchali M, Malekzadeh Viayeh R. [A study on geographical distribution and diversity of Lymnaeidae snails in West Azerbaijan province, Iran (Persian)]. Veterinary Research & Biological Products. 2011; 23(4):53-63. [Link]

- Faltýnková A, Nasincová V, Kablásková L. Larval trematodes (Digenea) of the great pond snail, Lymnaea stagnalis (L.),(Gastropoda, Pulmonata) in Central Europe: A survey of species and key to their identification. Parasite. 2007; 14(1):39-51. [DOI:10.1051/parasite/2007141039] [PMID]

- Brant SV, Loker ES. Molecular systematics of the avian schistosome genus Trichobilharzia (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae) in North America. Journal of Parasitology. 2009; 95(4):941-63. [DOI:10.1645/GE-1870.1] [PMID]

- Lotfy WM, Lotfy LM, Khalifa RM. An overview of cercariae from the Egyptian inland water snails. Journal of Coastal Life Medicine. 2017; 5(12):562-74 [DOI:10.12980/jclm.5.2017J7-161]

- Gerlach J. Short-term climate change and the extinction of the snail Rhachistia aldabrae (Gastropoda: Pulmonata). Biology Letters. 2007; 3(5):581-4. [DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0316] [PMID]

- Mouritsen KN, Tompkins DM, Poulin R. Climate warming may cause a parasite-induced collapse in coastal amphipod populations. Oecologia. 2005; 146(3):476-83. [DOI:10.1007/s00442-005-0223-0] [PMID]

- Imani-Baran A, Yakhchali M, Malekzadeh Viayeh R, Sehhatnia B, Darvishzadeh R. [Ecology of snail family Lymnaeidae and effects of certain chemial components on their distribution in aquatic habitats of West Azarbaijan, Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Veterinary Research. 2015; 70(4):433-40. [DOI:10.22059/JVR.2016.56464]

- Ashrafi K. [A survey on human and animal fascioliasis and genotypic and pHenotypic characteristics of fasciolids and their relationship with lymnaeid snails in Gilan province, northern Iran (Persian)] [PhD dissertation]. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2004.

- Karimi GR, Derakhshanfar M, Peykari H. Population density, trematodal infection and ecology of Lymnaea snails in Shadegan, Iran. Archives of Razi Institute. 2004. 58(1):125-9. [Link]

- Mansourian A, Rokni MB. Medical snailology. Tehran: Tabash Andisheh Publications; 2004.

- Harrison AD, Nduku W, Hooper AS. The effects of a high magnesium-to-calcium ratio on the egg-laying rate of an aquatic planorbid snail, BiompHalaria pfeifferi. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 1966; 60(2):212-4. [DOI:10.1080/00034983.1966.11686407] [PMID]

- Krist AC, Lively CM. Experimental exposure of juvenile snails (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) to infection by trematode larvae (MicropHallus sp.): Infectivity, fecundity compensation and growth. Oecologia. 1998; 116(4):575-82. [DOI:10.1007/s004420050623] [PMID]

- Soldánová M, Selbach C, Sures B, Kostadinova A, Pérez-Del-Olmo A. Larval trematode communities in Radix auricularia and Lymnaea stagnalis in a reservoir system of the ruhr river. Parasites & Vectors. 2010; 3:56. [DOI:10.1186/1756-3305-3-56] [PMID]

- Ofoezie IE. Distribution of freshwater snails in the man-made Oyan Reservoir, Ogun State, Nigeria. Hydrobiologia. 1999; 416:181-91. [DOI:10.1023/A:1003875706638]

- Farahnak A, Vafaie Darian I, Moubedi I. A faunistic survey of cercariae from fresh water snails: Melanopsis spp. and their role in disease transmission. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2006; 35(4):70-4. [Link]

- Nourpisheh SH. [The biology of Lymnea snail and its role in transmiting of infection to human and animal in Khoozestan province (Persian)] [MS thesis]. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences ; 1998.

- Faltýnková A, Haas W. Larval trematodes in freshwater molluscs from the Elbe to Danube rivers (Southeast Germany): Before and today. Parasitology Research. 2006; 99(5):572-82. [DOI:10.1007/s00436-006-0197-9] [PMID]

- Arfaa F, Sahba GH, Massoud J. The susceptibility of some Iranian snails to various local and foreign species of Trematodes. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 1973; 2(1):54-8. [Link]

- Kraus TJ, Brant SV, Adema CM. Characterization of trematode cercariae from physella acuta in the Middle Rio Grande. Comparative Parasitology. 2014; 81(1):105-9. [DOI:10.1654/4674.1]

- Schwelm J, Selbach C, Kremers J, Sures B. Rare inventory of trematode diversity in a protected natural reserve. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):22066. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-01457-2] [PMID]

- Aryaeipour M, Mansoorian AB, Rad MBM, Rouhani S, Pirestani M, Hanafi-Bojd AA, et al. Contamination of vector snails with the larval stages of trematodes in selected areas in northern Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2022; 51(6):1400. [DOI:10.18502/ijpH.v51i6.9697]

- Modabbernia G, Meshgi B, Rokni MB. A faunistic survey of snails and their infection with digenean trematode cercariae in Bandar-e Anzali at the littoral of the Caspian Sea. Annals of Parasitology. 2021; 67(4):703-13. [Link]

Review Paper: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2023/01/28 | Accepted: 2023/08/12 | Published: 2023/12/31

Received: 2023/01/28 | Accepted: 2023/08/12 | Published: 2023/12/31

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |