Volume 33, Issue 2 (6-2024)

JGUMS 2024, 33(2): 216-227 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohamadianamiri M, Sourati A, Aklamli M. Comparing the Therapeutic Effects of Boric Acid and Fluconazole in the Treatment of Vaginal Candidiasis. JGUMS 2024; 33 (2) :216-227

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2626-en.html

URL: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2626-en.html

1- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Endometriosis Research Center, School of Medicine, Shahid Akbar-Abadi Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Radiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Anesthesiology, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Radiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Anesthesiology, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 3783 kb]

(329 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2014 Views)

Full-Text: (4749 Views)

Introduction

Vaginal discharge is one of the common reasons for seeking consultation in women. The female reproductive system has a complex microbial flora where many physiological and pathological changes can be observed depending on various factors including age, menstrual period and the use of oral contraceptives. Physiologic vaginal discharge is colorless or white, odorless and without consequences. Studies have shown that the most common causes of abnormal vaginal discharge are candida vaginitis, bacterial vaginitis, and trichomoniasis [1, 2, 3]. Diagnosis of candidal vaginitis is based on the patient’s symptoms, accurate microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions and evaluation of vaginal pH [4]. Approved treatments for this disease, which contributes to 41.4% of vaginitis, include a wide range of topical antifungal drugs that are typically used for 1-3 days as well as oral fluconazole 150 mg. Both topical and oral azole drugs cause relief of symptoms and negative culture in 80-90% of patients [5, 6, 7]. The treatments used today for chronic and recurrent fungal vaginitis infections are experimental. A one-week treatment with fluconazole can reduce the recurrence rate of vaginal candidiasis [8, 9]. The principles of the treatment are first based on complete treatment, and then maintenance treatment up to six months. Discontinuing the treatment in 50% of patients leads to the return of the infection. In treatment-resistant infections, auxiliary drugs such as ketoconazole and itraconazole should be used along with fluconazole. Considering the importance of knowing the best method of treatment in patients with candidal vaginitis, clinical trials are of particular importance. Considering the importance of the topic, this clinical trial aims to compare the effectiveness of boric acid and fluconazole and their side effects in the treatment of candidal vaginitis to the appropriate treatment method.

Methods

This is a non-blind randomized clinical trial that was conducted from November 2021 to January 2022 on 50 women with candidal vaginitis based on clinical and microbiological examinations who referred to hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences. Patients underwent clinical examination, direct smear of secretions, and cultures of secretions, and were included in the study if candidal vaginitis was confirmed. The observation of cheesy secretions, erythema, edema was considered as an inflammatory sign. Vaginal swab was performed for direct smear and secretion culture. Diagnosis and confirmation of patients’ vaginitis based on the patient’s symptoms, accurate microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions in the laboratory, quantitative evaluation of white blood cells and evaluation of vaginal pH were also performed [4]. Identification of Candida species was done by colony morphology, germ tube test, hypha morphology and chlamydospore formation on corn meal agar, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride test, fermentation and absorption of different sugars, and sensitivity test to cycloheximide.

The sample size was determined according to the results of Ray et al. [28] and based on the formula, considering α=0.05, β=0.2, P1=0.6, and P2=0.3. Based on the results, 46 women in two groups of 23 were considered. With an increase of 10% due to possible sample dropout, 25 people were considered for each group. After confirmation of candidal vaginitis, 46 women were included in the study and 4 were excluded. The obtained information was analyzed in SPSS software, version 26. In the descriptive analysis, frequency, percentage, and Mean±SD, were used. To determine the difference between the two groups and also between the two evaluation phases in two groups, chi-square test was used.

Results

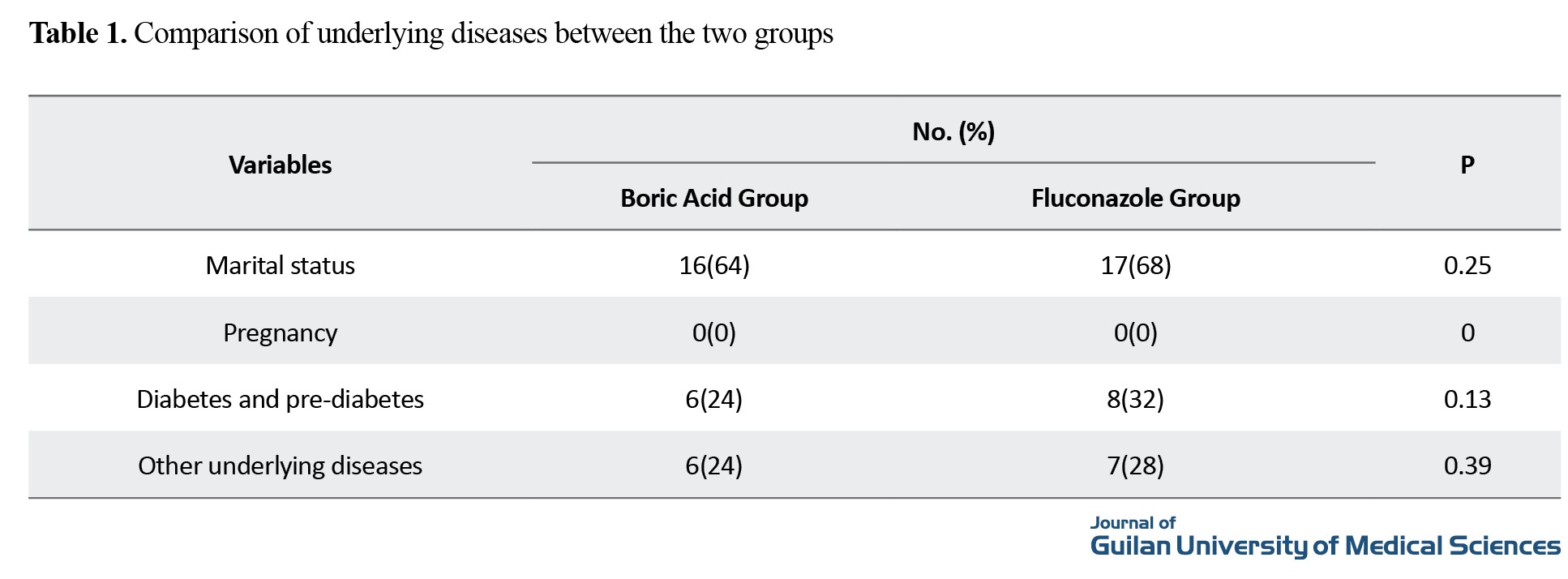

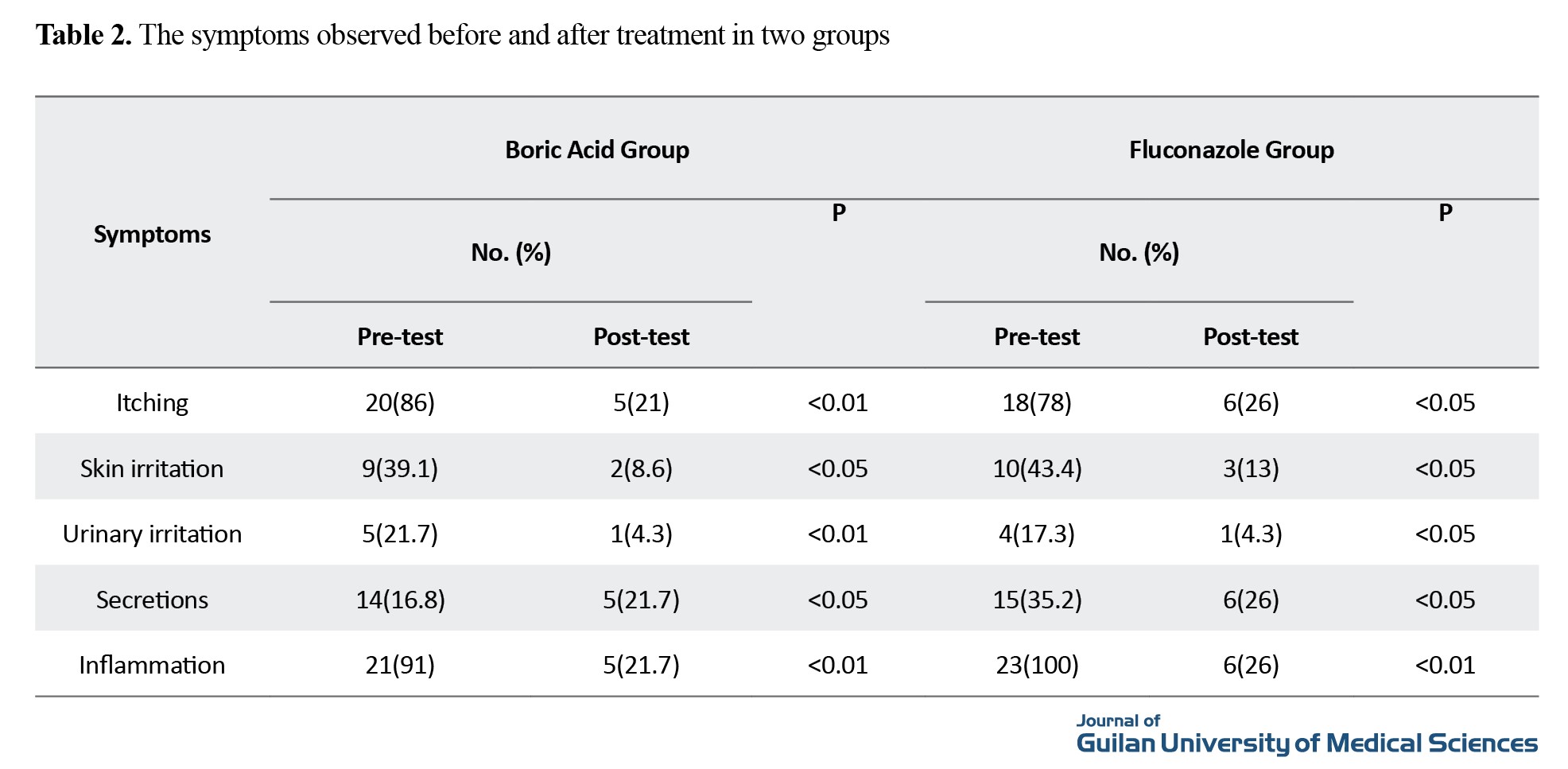

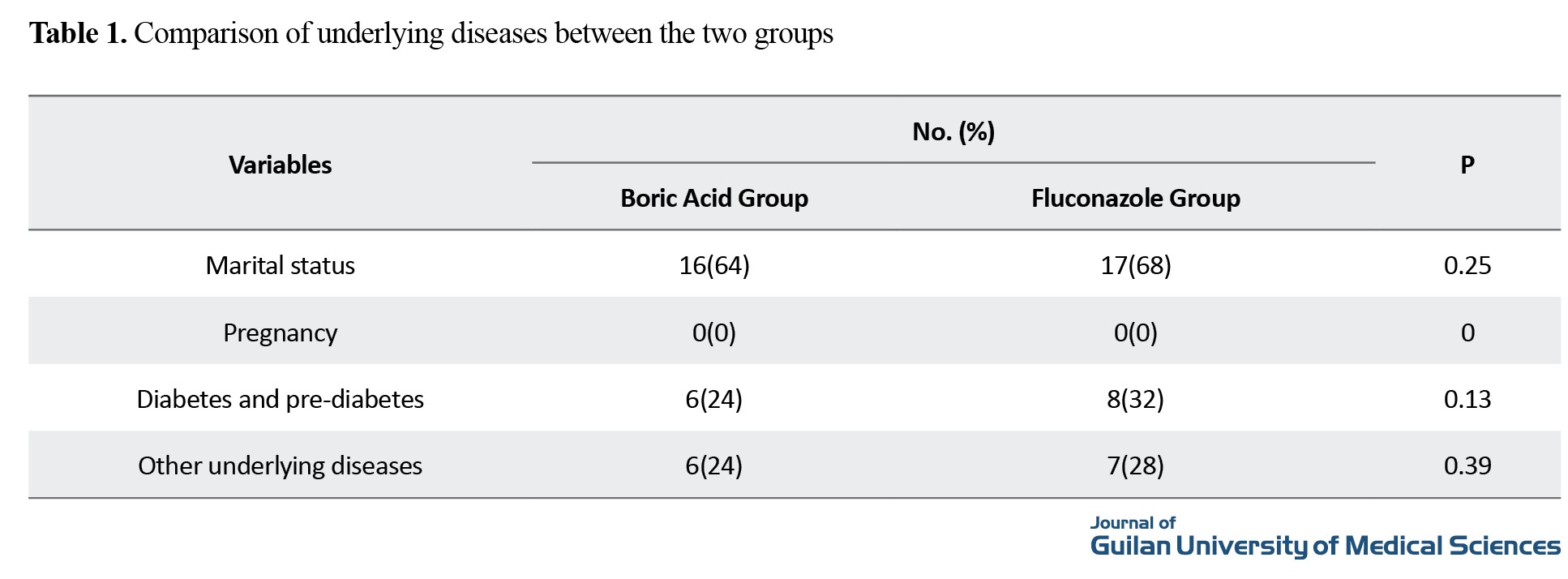

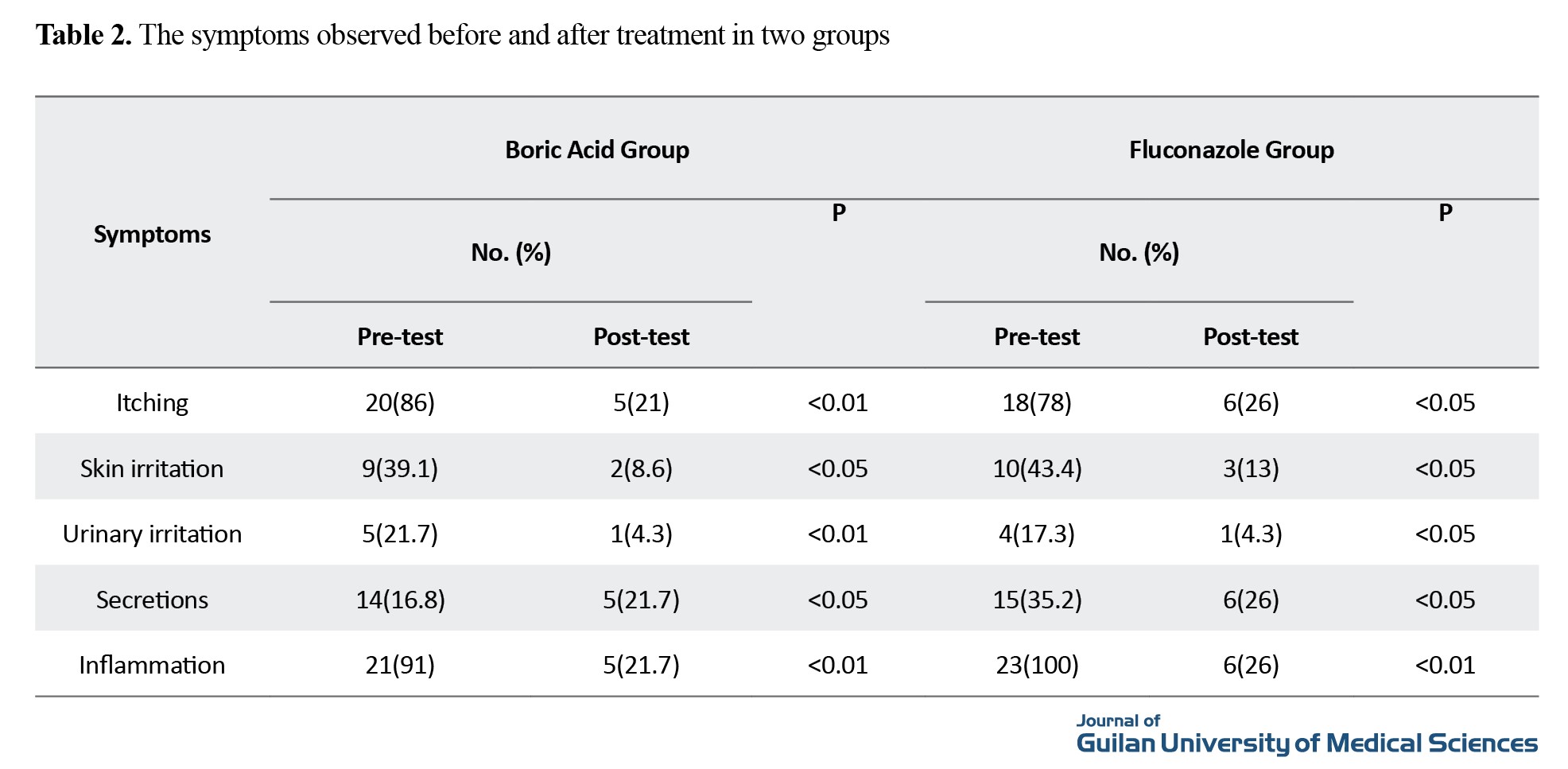

The mean age in the boric acid group was 32±5.88 years, and in the fluconazole group as 31.5±3.85 years. The body mass index was 27.9 in the boric acid group and 27.1 in the fluconazole group. The comparison of underlying diseases is shown in Table 1, and the prevalence of symptoms before and after treatment in both groups is shown in Table 2.

Side effects of fluconazole use included gastrointestinal side effects among 3 women (13%) while the side effects of boric acid use included burning and skin side effects among 2 women (8.6%), and this difference was not significant (P>0.05).

In the boric acid group, 5 women had a positive culture after the treatment period (78% treatment response). In the fluconazole group, 7 women had a positive culture after the treatment period (69.5% treatment response). It shows the relative superiority of boric acid in improving the results of culture. Among 7 patients who still had positive cultures after the end of fluconazole treatment, 5 had diabetes and pre-diabetes (71%). Among 5 patients who still had positive cultures after finishing the treatment with boric acid, 3 had diabetes and pre-diabetes (40%). This shows the more suitable effect of boric acid in patients with diabetes and relative resistance to fluconazole in diabetic patients.

Conclusion

The rate of treatment success in the boric acid group was higher than in the fluconazole group and with fewer side effects, which indicated the superiority of boric acid. The percentage of improvement after treatment with boric acid is 78.2% and after treatment with fluconazole is 69.5%. The results of this study indicate the clinical use of boric acid as the first-line treatment for women with candidal vaginitis.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research and Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.389).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mahdiss Mohamadianamiri; Methodology and project administration: Majid Aklamli: Writing: Ainaz Sourati.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Vaginal discharge is one of the common reasons for seeking consultation in women. The female reproductive system has a complex microbial flora where many physiological and pathological changes can be observed depending on various factors including age, menstrual period and the use of oral contraceptives. Physiologic vaginal discharge is colorless or white, odorless and without consequences. Studies have shown that the most common causes of abnormal vaginal discharge are candida vaginitis, bacterial vaginitis, and trichomoniasis [1, 2, 3]. Diagnosis of candidal vaginitis is based on the patient’s symptoms, accurate microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions and evaluation of vaginal pH [4]. Approved treatments for this disease, which contributes to 41.4% of vaginitis, include a wide range of topical antifungal drugs that are typically used for 1-3 days as well as oral fluconazole 150 mg. Both topical and oral azole drugs cause relief of symptoms and negative culture in 80-90% of patients [5, 6, 7]. The treatments used today for chronic and recurrent fungal vaginitis infections are experimental. A one-week treatment with fluconazole can reduce the recurrence rate of vaginal candidiasis [8, 9]. The principles of the treatment are first based on complete treatment, and then maintenance treatment up to six months. Discontinuing the treatment in 50% of patients leads to the return of the infection. In treatment-resistant infections, auxiliary drugs such as ketoconazole and itraconazole should be used along with fluconazole. Considering the importance of knowing the best method of treatment in patients with candidal vaginitis, clinical trials are of particular importance. Considering the importance of the topic, this clinical trial aims to compare the effectiveness of boric acid and fluconazole and their side effects in the treatment of candidal vaginitis to the appropriate treatment method.

Methods

This is a non-blind randomized clinical trial that was conducted from November 2021 to January 2022 on 50 women with candidal vaginitis based on clinical and microbiological examinations who referred to hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences. Patients underwent clinical examination, direct smear of secretions, and cultures of secretions, and were included in the study if candidal vaginitis was confirmed. The observation of cheesy secretions, erythema, edema was considered as an inflammatory sign. Vaginal swab was performed for direct smear and secretion culture. Diagnosis and confirmation of patients’ vaginitis based on the patient’s symptoms, accurate microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions in the laboratory, quantitative evaluation of white blood cells and evaluation of vaginal pH were also performed [4]. Identification of Candida species was done by colony morphology, germ tube test, hypha morphology and chlamydospore formation on corn meal agar, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride test, fermentation and absorption of different sugars, and sensitivity test to cycloheximide.

The sample size was determined according to the results of Ray et al. [28] and based on the formula, considering α=0.05, β=0.2, P1=0.6, and P2=0.3. Based on the results, 46 women in two groups of 23 were considered. With an increase of 10% due to possible sample dropout, 25 people were considered for each group. After confirmation of candidal vaginitis, 46 women were included in the study and 4 were excluded. The obtained information was analyzed in SPSS software, version 26. In the descriptive analysis, frequency, percentage, and Mean±SD, were used. To determine the difference between the two groups and also between the two evaluation phases in two groups, chi-square test was used.

Results

The mean age in the boric acid group was 32±5.88 years, and in the fluconazole group as 31.5±3.85 years. The body mass index was 27.9 in the boric acid group and 27.1 in the fluconazole group. The comparison of underlying diseases is shown in Table 1, and the prevalence of symptoms before and after treatment in both groups is shown in Table 2.

Side effects of fluconazole use included gastrointestinal side effects among 3 women (13%) while the side effects of boric acid use included burning and skin side effects among 2 women (8.6%), and this difference was not significant (P>0.05).

In the boric acid group, 5 women had a positive culture after the treatment period (78% treatment response). In the fluconazole group, 7 women had a positive culture after the treatment period (69.5% treatment response). It shows the relative superiority of boric acid in improving the results of culture. Among 7 patients who still had positive cultures after the end of fluconazole treatment, 5 had diabetes and pre-diabetes (71%). Among 5 patients who still had positive cultures after finishing the treatment with boric acid, 3 had diabetes and pre-diabetes (40%). This shows the more suitable effect of boric acid in patients with diabetes and relative resistance to fluconazole in diabetic patients.

Conclusion

The rate of treatment success in the boric acid group was higher than in the fluconazole group and with fewer side effects, which indicated the superiority of boric acid. The percentage of improvement after treatment with boric acid is 78.2% and after treatment with fluconazole is 69.5%. The results of this study indicate the clinical use of boric acid as the first-line treatment for women with candidal vaginitis.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research and Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.389).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mahdiss Mohamadianamiri; Methodology and project administration: Majid Aklamli: Writing: Ainaz Sourati.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Mullick S, Watson-Jones D, Beksinska M, Mabey D. Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy: Prevalence, impact on pregnancy outcomes, and approach to treatment in developing countries. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005; 81(4):294-302. [DOI:10.1136/sti.2002.004077] [PMID]

- Becker M, Stephen J, Moses S, Washington R, Maclean I, Cheang M, et al. Etiology and determinants of sexually transmitted infections in Karnataka State, south India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010; 37(3):159-64. [DOI:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bd1007] [PMID]

- Prasad D, Parween S, Kumari K, Singh N. Prevalence, etiology, and associated symptoms of vaginal discharge during pregnancy in women seen in a tertiary care Hospital in Bihar. Cureus. 2021;13(1). [DOI:10.7759/cureus.12700]

- Sparks JM. Vaginitis. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1991; 36(10):745-52. [PMID]

- Sobel JD. Pathogenesis of Candida vulvovaginitis. Current Topics in Medical Mycology. 1989; 3:86-108. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4612-3624-5_5] [PMID]

- Bitew A, Abebaw Y. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Species distribution of Candida and their antifungal susceptibility pattern. BMC Women's Health. 2018; 18(1):94. [DOI:10.1186/s12905-018-0607-z] [PMID]

- Maraki S, Mavromanolaki VE, Stafylaki D, Nioti E, Hamilos G, Kasimati A. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida isolates from Greek women with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycoses. 2019; 62(8):692-7. [DOI:10.1111/myc.12946] [PMID]

- Fakhim H, Vaezi A, Javidnia J, Nasri E, Mahdi D, Diba K, et al. Candida Africana vulvovaginitis: Prevalence and geographical distribution. Journal de Mycologie Médicale. 2020; 30(3):100966. [DOI:10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.100966] [PMID]

- Zeng X, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Xue Y, Xu H, An R. Risk factors of vulvovaginal Candidiasis among women of reproductive age in Xi'an: A cross-sectional study. BioMed Research International. 2018; 2018:9703754. [DOI:10.1155/2018/9703754] [PMID]

- Blostein F, Levin-Sparenberg E, Wagner J, Foxman B. Recurrent vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2017; 27(9):575-82.e3. [DOI:10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.08.010] [PMID]

- Foxman B, Muraglia R, Dietz JP, Sobel JD, Wagner J. Prevalence of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in 5 European countries and the United States: Results from an internet panel survey. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2013; 17(3):340-5. [DOI:10.1097/LGT.0b013e318273e8cf] [PMID]

- Yano J, Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, Sobel R, Williams VL, Yu Q, et al. Current patient perspectives of vulvovaginal candidiasis: incidence, symptoms, management and post-treatment outcomes. BMC Women's Health. 2019; 19(1):48. [DOI:10.1186/s12905-019-0748-8] [PMID]

- Story K, Sobel R. Fluconazole prophylaxis in prevention of symptomatic candida vaginitis. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2020; ;22(1):2. [DOI:10.1007/s11908-020-0712-7] [PMID]

- Lu H, Shrivastava M, Whiteway M, Jiang Y. Candida albicans targets that potentially synergize with fluconazole. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2021; 47(3):323-37. [DOI:10.1080/1040841X.2021.1884641] [PMID]

- Egunsola O, Adefurin A, Fakis A, Jacqz-Aigrain E, Choonara I, Sammons H. Safety of fluconazole in paediatrics: A systematic review. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2013; 69(6):1211-21. [DOI:10.1007/s00228-012-1468-2] [PMID]

- Goje O. Genitourinary Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. In: Jonathan S. Berek DLB, editor. Berek & Novak's Gynecology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2020.

- van Schalkwyk J, Yudin MH; INFECTIOUS DISEASE COMMITTEE. Vulvovaginitis: Screening for and management of trichomoniasis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and bacterial vaginosis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2015; 37(3):266-74. [DOI:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30316-9] [PMID]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016; 62(4):e1-50. [DOI:10.1093/cid/civ933] [PMID]

- Sobel JD, Chaim W, Nagappan V, Leaman D. Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: Use of topical boric acid and flucytosine. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003; 189(5):1297-300. [DOI:10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00726-9] [PMID]

- Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Zarkada IM, Falagas ME. Boric acid for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: The clinical evidence. Journal of Women's Health. 2011; 20(8):1245-55. [DOI:10.1089/jwh.2010.2708] [PMID]

- Prutting SM, Cerveny JD. Boric acid vaginal suppositories: A brief review. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998; 6(4):191-4. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1098-0997(1998)6:43.0.CO;2-6] [PMID]

- De Seta F, Schmidt M, Vu B, Essmann M, Larsen B. Antifungal mechanisms supporting boric acid therapy of Candida vaginitis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009; 63(2):325-36. [DOI:10.1093/jac/dkn486] [PMID]

- Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. The Lancet. 2007; 369(9577):1961-71. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9] [PMID]

- Collins LM, Moore R, Sobel JD. Prognosis and long-term outcome of women with idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by Candida albicans. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2020; 24(1):48-52. [DOI:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000496] [PMID]

- Gunther LS, Martins HP, Gimenes F, Abreu AL, Consolaro ME, Svidzinski TI. Prevalence of Candida albicans and non-albicans isolates from vaginal secretions: Comparative evaluation of colonization, vaginal candidiasis and recurrent vaginal candidiasis in diabetic and non-diabetic women. São paulo Medical Journal. 2014; 132(2):116-20. [DOI:10.1590/1516-3180.2014.1322640] [PMID]

- Crouss T, Sobel JD, Smith K, Nyirjesy P. Long-term outcomes of women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis after a course of maintenance antifungal therapy. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2018; 22(4):382-6. [DOI:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000413] [PMID]

- Hadrup N, Frederiksen M, Sharma AK. Toxicity of boric acid, borax and other boron containing compounds: A review. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2021; 121:104873. [DOI:10.1016/j.yrtph.2021.104873] [PMID]

- Ray D, Goswami R, Banerjee U, Dadhwal V, Goswami D, Mandal P, et al. Prevalence of Candida glabrata and its response to boric acid vaginal suppositories in comparison with oral fluconazole in patients with diabetes and vulvovaginal candidiasis. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(2):312-7. [DOI:10.2337/dc06-1469] [PMID]

- Nyirjesy P, Brookhart C, Lazenby G, Schwebke J, Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: A review of the evidence for the 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2022; 74(Supplement_2):S162-8. [DOI:10.1093/cid/ciab1057] [PMID]

- Kalia N, Singh J, Kaur M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: A critical review. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2020; 19(1):5. [DOI:10.1186/s12941-020-0347-4] [PMID]

- Redondo-Lopez V, Lynch M, Schmitt C, Cook R, Sobel JD. Torulopsis glabrata vaginitis: Clinical aspects and susceptibility to antifungal agents. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1990; 76(4):651-5. [PMID]

- Sobel JD, Chaim W. Treatment of Torulopsis glabrata vaginitis: Retrospective review of boric acid therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997; 24(4):649-52. [DOI:10.1093/clind/24.4.649] [PMID]

- Swate TE, Weed JC. Boric acid treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1974; 43(6):893-5. [PMID]

- Schmidt M, Tran-Nguyen D, Chizek P. Influence of boric acid on energy metabolism and stress tolerance of Candida albicans. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2018; 49:140-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.05.011] [PMID]

- Salama OE, Gerstein AC. Differential response of Candida species morphologies and isolates to fluconazole and boric acid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2022; 66(5):e02406-21. [DOI:10.1128/aac.02406-21] [PMID]

- Kalkan Ü, Yassa M, Sandal K, Teki̇ A, Kilinç C, Gülümser Ç, et al. The efficacy of the boric acid-based maintenance therapy in preventing recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine. 2021; 38(4):461-5. [DOI:10.52142/omujecm.38.4.11]

- Sobel J, Sobel R. Current treatment options for vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by azole-resistant Candida species. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2018; 19(9):971-7. [DOI:10.1080/14656566.2018.1476490] [PMID]

- Marchaim D, Lemanek L, Bheemreddy S, Kaye KS, Sobel JD. Fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans vulvovaginitis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012; 120(6):1407-14. [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827307b2] [PMID]

Review Paper: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2023/08/5 | Accepted: 2024/02/14 | Published: 2024/07/1

Received: 2023/08/5 | Accepted: 2024/02/14 | Published: 2024/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |